There was a country that was occupied several years ago and I still think it is, no matter how much time goes on. It is multiply occupied at the lowest level, like a Bose-Einstein Condensate. Folks there have had three regime changes in the past generation. To communism, to Mislamism and to TWATism.

The Meddlers just wont leave them to re-equilibriate. Their deluded, culturally conditioned Meddler's Logic leads them to believe that they are part of the future resolution of the problem and must stay there for the 'long haul', lest 'chaos' occur.

At present the group in internationally recognised power cannot provide basic security for the people without their headhunter's stick and carrot peelings. It is a fundamental problem, because they cannot face their old enemy face to face, emerge on top, depersonalise it and move on united.

Face to face one achieves the practical demonstration of one's fitness for government. Without that any crumb you are given is a false sense of custodianship. These backdoor transplanted regimes are effete, lack mojo and bring disgrace upon their noble qaums. On top of this you have squads of second rate NGO workers transplanting confused ideas, in fancy dress, to bribe the people with petty solutions that pass for development these days. The resultant picture is a fake state and a fake 'civil' 'society' of hired hands and people promoted into incompetence.

What ever happened to that ancient of lessons. The one where you recognise your inadequacy, vacate the space and have the good sense not to pollute it with your dirty mind, interests and money any longer?

27.2.08

25.2.08

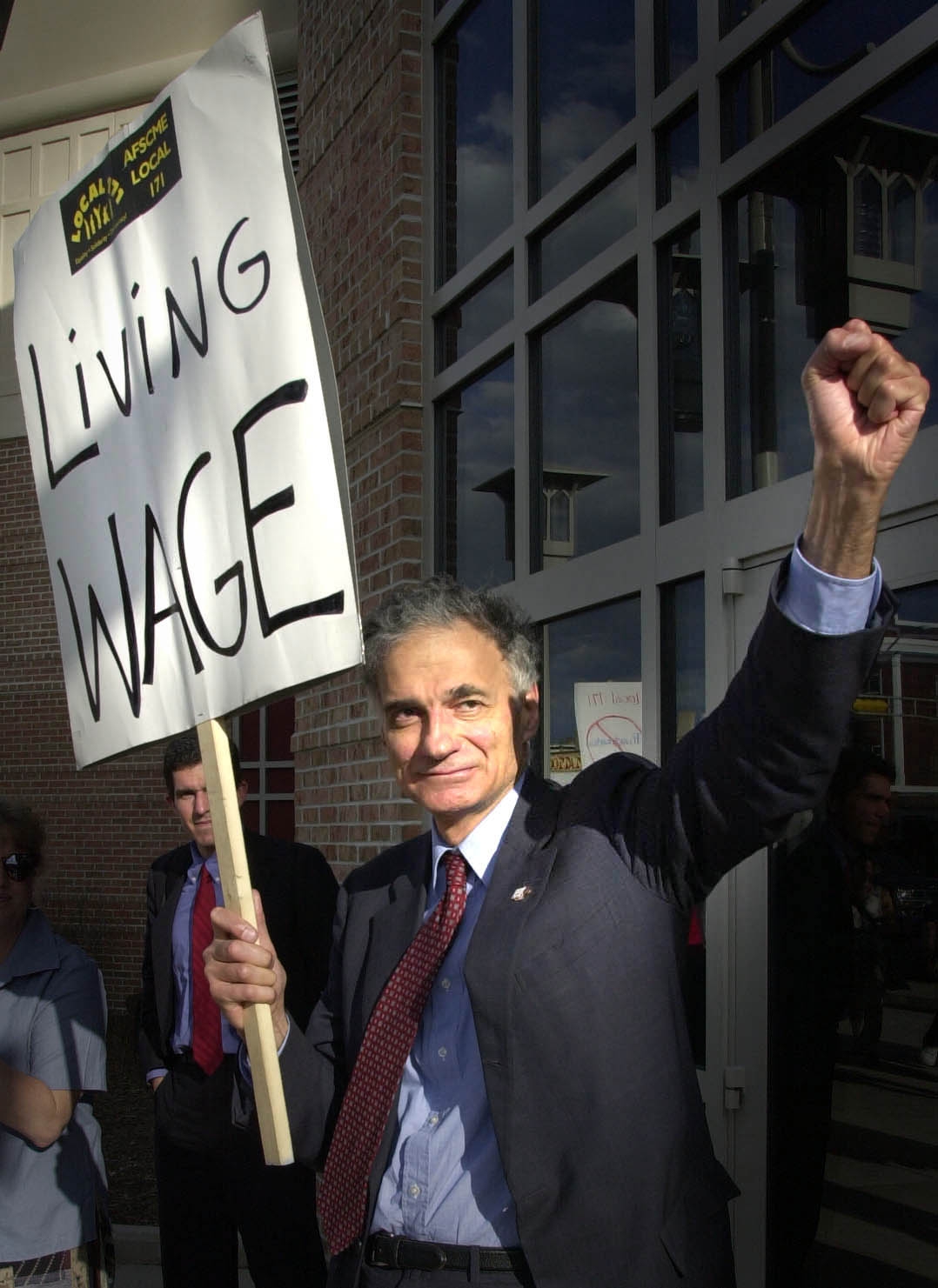

Ralph Nader is running.

So he is one of the coolest men on this earth and has shown us youngies what consumer activism can be. He has decided to run for President again. His Campaign website is here. In the article below witness his uncommon wisdom on the issue of him 'robbing the democrats of victory' and on 'the only ageing is the erosion of principles'. The manner of Obama's comment on Nader's standards being too high for anybody to meet was neat.

Here is an article from the NYT political blog. If I were relevant to the leadership choice, I would put my loyalty with Nader, join the campaign and learn some spineful political craft from the murrabi (elder).

Here is an article from the NYT political blog. If I were relevant to the leadership choice, I would put my loyalty with Nader, join the campaign and learn some spineful political craft from the murrabi (elder).

Some of the folks being creative and on the Democrat side have sent a message to Nader. I don't agree with the sentiment, but it's amusing nonetheless. Sad how its not just salafis who seem bound by conscience to suffocate civilisational improvement.

21.2.08

[Farhad Mazhar] Language, ecology and knowledge practice.

There are a lot of distraction tactics and power games concerning language in Bangladesh. It was a potent symbol around which a lot of people were mobilised in the past. In their overzealousness and thickness some planners arranged it so the standard of english dropped significantly in the immediate post independance phase and multiliguality.. i think needs to be researched far more. I'm not sure there has been a 'renaissance' amongst the bengali muslim qaum since. I think folks would like some form of blossoming period but judgeing from the bad points of the three educational streams, the sheer and crass lack of elite interest fusing the streams....it is hard to imagine.

Many Bangladeshis consider it a sign of their cultural virility that the UN administration system considers today international mother language day. I suppose its quite neat for those who died for it and those who nearly worship those who died for it. Personally I'm more interested in the generation and refinement of ideas and mojo to address the needs of the people. That is there Farhad Mazhar comes in.

This article was in todays NewAge paper and is coming from one of the few deshi people with some mojo left and prowess in experimental discovery. From what ive been able to tell, he walks his talk. Though the whole bio-diverse agriculture thing really isnt my scene i'm really glad that issues of knowledge culture, practice and the limits of crass language nationalism are being raised when many will be getting drunk on state ideology. I have summarised (though probably misunderstood) his argument below.

Language, ecology and knowledge practice

The cultural and knowledge practices of a community who have been historically feeding us and maintaining ecology and environment for the future generations have done all their innovations, thinking and memorisation in a dialect that is specific and experiential. It is crucial that we turn our interest to this issue before it is too late, writes Farhad Mazhar

OUR matribhasha (mother tongue) is Bangla. The literal meaning of matribhasha is the dialect my mother uses to communicate; the oral or vocal sign system she uses to represent her ideas or command others to performative tasks. The Bangla I learned from my mother is not the Bangla of urban elite, not bhadroloker bhasha; such verbal behaviours were known to us in the childhood as the kolkaityawalader bhasha – language of the class engaged in commerce with the colonial city of Kolkata. A language that is considered not authentic, not from the linguistic sensuousness that reveals the world around us in signs and metaphors, but a language developed for a very specific or particular purpose: commerce.

My mother used to speak in pure Noakhailya language, the language of the people of Noakhali, full of wit, humour and subtle metaphor. This is my matribhasha, my mother tongue. While she used to express her love in Noakhailya language for her children she could articulate the words and sentences in such a way that I still claim with my Noakhailya chauvinism that none could express motherly affection except in sweet Noakhailya language. I grew up loving this beautiful language and soon noticed that every dialect has certain unique quality that is intricately connected with social formation, ecology, and history and above all cultural and knowledge practices. Knowing this fact did not hurt my Noakhailya pride; rather, over the years, the more I studied language the more I had to accept this truth with humility and profound interest to other dialects. Without being told by anthropologists or cultural historians, one can easily notice that language or speech acts are different by different communities as well as by status, class, and gender or by other determining factors. These facts are more or less known to social linguistics, however, the connection between language, ecology and knowledge practice is an area that has only recently come to attract attention.

I now work very closely on a day-to-day basis with farming communities engaged in biodiversity-based ecological agriculture. Bio-diverse agrarian practices are rich historical traditions of this deltaic country. The wealth, richness and global significance of such practices are only recently revealed because of advance in biological and molecular science. More these connections are studied and brought to the mainstream more they open up possibility of ensuring new advance in science and technology based on farmer-led research. Such research is able to ensure food sovereignty of Bangladesh, but perhaps also the other countries at the same time since creating bio-diverse ecological environment for the maximisation of the productivity potential of nature is not dependent on ‘gene’ but to the total environment where traits are expressed.

Bangladesh is rich in biodiversity and the potentiality of nature is simply phenomenal, if we learn how to unleash her power. However, that is not possible by industrial food production system, it implies we must move away from the environmentally-destructive chemicals including fertilisers, pesticides or biocides and it is criminal to waste our water resources in the aquifer polluting environment and health with arsenic contamination. This is what the present military-backed regime is doing, an insane path that sooner or later will permanently destroy our agriculture, while there are ample evidence that advance bio-diverse agrarian practices are possible to grow more food, fibre, medicines, fuel wood and construction materials. This will require that we ground our science and technology practice on the authentic foundation of a knowledge system developed within the ecological paradigm of Bengal, and not on industrial food production controlled by few trans-national corporations of the world.

Bangladesh is already bleeding because of the piracy of the rich biological resources and now the present ‘caretakers’ are rapidly engaged in destruction of the agrarian foundation by violently transforming rural areas into plundering grounds for seed companies, technology vendors and NGOs who are selling proprietary seeds and forcing farmers to accept those on (micro)-credit. With the support of the anti-people regime, not accountable to the people, they are powerfully manipulating the media claiming that commercial hybrid seeds are the solution of our food problem. These seeds need massive chemicals, pesticides and groundwater and totally destroying the existing seed system of the farmer upon which the agrarian production and economy has historically been dependent. The destruction the present policy of the ‘caretakers’ will eventually be a nightmare for Bangladesh, as well as for the ‘development partners’. These are issues that need to be addressed more in detail separately, but I raised the issue to highlight a point that we hardly can see: the connection between ecology, environment, culture and agrarian civilisation.

The dominance of the so called ‘promit’ Bangla also signifies erosion of our knowledge depositories that are embedded in our rural oral culture. What I would like to argue is that the idea of ‘language’ as a homogenous standard system that one learns from schools reading textbooks and the implicit notion of ‘education’ that implies unlearning the oral linguistic practices or local dialects is a dangerous notion indeed. The cultural and knowledge practices of a community who have been historically feeding us and maintaining ecology and environment for the future generations have done all their innovations, thinking and memorisation in a dialect that is specific and experiential. It is crucial that we turn our interest to this issue before it is too late.

When I need words to express or articulate agrarian practices or ecological or environmental terms, the literary Bangla is poor compared to the language that the farmers use. I wonder whether the dominance of the language of a particular class also creates conditions for environmental and ecological erosion. Local language and the knowledge practices of a community are crucial for survival. Once we realise the security and survival issues we could also understand why literary Bangla, or as it is called ‘promit” or standard Bangla, which grew within the commercial milieu of colonial Calcutta, is termed ‘commercial Bangla’ by agrarian communities I know very intimately. It is a form of cultural resistance against the processes of erosion and decay of knowledge practice embedded in oral communicative dynamics and stands in opposition to printing or standard texts.

To provide a simple glimpse of what we are talking about, we can simply take note of the various names of rice varieties used by farming communities; they surprise anyone because of linguistic innovation, taxonomic classification and metaphoric implication. Naming seed varieties is simply a phenomenal and brilliant act and scientifically could also be used as ecological descriptor in contrast to the breeders descriptors used by scientists trained in industrial food production. As a genuine student of the farmers the farming community awarded me with immense learning appropriate for agriculture, ecology and environment. Imagine, we had, as scientists claimed, nearly 15,000 varieties of rice.

However, some scientists argue that genetically speaking they are much less, since the same variety is named differently in different areas. It does not mean that such farmers’ lot, co-evolved with other species and varieties in farming practices are ‘same’. What these scientists are totally missing is the multiplicity in varietals or gene expression of a variety in a particular environment, ecology and farming practices – a knowledge that are extremely vital to develop agrarian planning, production, knowledge practices and culture. So the farmers’ name does not suggest so-called ‘pure line’ or pure variety – but knowledge of a variety that expresses differently in different environments.

This is the reason why ecological scientists in contrast to the industrial food producers and the trans-national corporations make scientific distinction between ‘breeders’ descriptor and ecological descriptor. The former is integral to industrial food production systems while ecological ‘descriptors’ are related to bio-diverse farming practices. These are names or categories used to capture the nuances of ecological, environmental and biological richness and wealth of our agriculture. The latter captures the ‘whole’ in unique environment while the former manipulates part – ‘genes’. The farmer’s movement that I am now involved with, known as Nayakrshi Andolon, cultivates nearly 2000 varieties of rice. Imagine, all these varieties has ‘name’ – all in Bangla, implying sharp or subtle nuances that could be used as ecological descriptor and key to the understanding of biodiversity-based ecological farming practices.

If language is part and parcel of diverse knowledge and cultural practices and product of social interactions where ‘commerce’ is only one of the socialising contexts or specific form of interaction – the overemphasis on the ‘standard Bangla’ or promit Bangla is to be seen as question related to class and power. Rightly, standard or promit bangla came into being as the product of colonialisation, capitalism and urbanisation that also produced a particular class and their literatures, imaginations, knowledge practices and class power. The historically specific form such interaction obtained is also directly linked with Gutenberg’s invention, i.e. printing technology. Communities imagining them as belonging to a ‘nation’ composed of ‘people’ or ‘population’ conceptualised in abstract, is very recent indeed. Nationalism or imagining ourselves belonging to an identity determined by language, homogenised culture or ‘nation’ directly contradicts the experiential perception of rural communities where people do not exist in abstract, not as number or population, but with specific names with parental link and places. Such imagining a population as ‘abstract’ nation is determined by the rise of the market and the printing technology.

If we understand differences as historically or contextually determined, we hardly need to argue. My argument here is not that whether we should not be imagining ‘nation’ and remain eternally bound to rural consciousness. My point is much more simpler: (a) from such historical understanding one cannot conclude imagining ourselves as ‘nation’ in any way proves a ‘progressive’ consciousness or in other words place-bound and experiential consciousness of farming communities are ‘backward; (b) that idea of language as a homogeneous phenomenon is problematical.

Having said this I do not conclude that ‘promit’ Bangla is something ‘bad’ that we should avoid, rather what we should do is activate a dynamic relation between the rich depository of knowledge in the our local dialects and weight of standardisation and homogenisation. Dr Shahidullah is the only person I know is determined to highlight the importance of local dialects. He was right, simply because he insisted that language is a living phenomenon and not a static affair. His dictionary on local language is a phenomenal step in exploring knowledge inscribed in local terms and notions. The critique of promit Bangla is not to argue that we should write and communicate only in local dialect. These are sterile logic and facile arguments. Language by nature belongs to our creative faculty and we must keep on exploring the language in many different ways since human communities are immensely creative.

My idea of matribhasha has nothing to do with the politics of identity. I am a nationalist only to the extent it contributes to the diversity of communities, nations, languages, cultures in order to constitute a global community. My interest in living local dialects is dictated by my interest in ecology, experiential knowledge and innovative knowledge practices that can invent, reproduce and maintain and thousands species and varieties in our ecosystems. I will not deny that I have some elements of chauvinism for such a rich bio-diverse agrarian culture and indeed I am proud of our farming communities since they are the one who understand from an immediate and experiential stance what does it mean by ‘matribhasha’.

Many Bangladeshis consider it a sign of their cultural virility that the UN administration system considers today international mother language day. I suppose its quite neat for those who died for it and those who nearly worship those who died for it. Personally I'm more interested in the generation and refinement of ideas and mojo to address the needs of the people. That is there Farhad Mazhar comes in.

This article was in todays NewAge paper and is coming from one of the few deshi people with some mojo left and prowess in experimental discovery. From what ive been able to tell, he walks his talk. Though the whole bio-diverse agriculture thing really isnt my scene i'm really glad that issues of knowledge culture, practice and the limits of crass language nationalism are being raised when many will be getting drunk on state ideology. I have summarised (though probably misunderstood) his argument below.

- My mother tongue is not the language of calcutta, how dare you try that one on me you crass nationalist.

- Ive spent time studying the nuances of the noakhali dialect and theres a local practical knowledge system embedded that would be lost by the imposition of 'shodho'.

- I work in ecological agriculture, in the ganj, we need to develop our local knowledge practices to acheive food sovereignty.

- The current governmental paradigm of agricultural research is destroying us. Our science and technology practice needes an authentic foundation. these caretakers are nuts (possibly a rift wrt CS Karim there)

- Development is an ugly lie and oh you development partners, the Caretaker government will make fools of you.

- The imporsition of uniform bengali, chaste bengal for calcutta, developed from colonial commerce culture is eroding the rural oral culture fo knowledge. Textbooks are rubbish and not useful for innovating in practice.

- I have learnt heeps from my teachers, the farmers. Check out Nayakrishi Andolon (New Farmer's Movement).

- We need to realise the rich depository of knowledge in the local dialects, and that language is live, not a pre-recorded phenomena.

Language, ecology and knowledge practice

The cultural and knowledge practices of a community who have been historically feeding us and maintaining ecology and environment for the future generations have done all their innovations, thinking and memorisation in a dialect that is specific and experiential. It is crucial that we turn our interest to this issue before it is too late, writes Farhad Mazhar

OUR matribhasha (mother tongue) is Bangla. The literal meaning of matribhasha is the dialect my mother uses to communicate; the oral or vocal sign system she uses to represent her ideas or command others to performative tasks. The Bangla I learned from my mother is not the Bangla of urban elite, not bhadroloker bhasha; such verbal behaviours were known to us in the childhood as the kolkaityawalader bhasha – language of the class engaged in commerce with the colonial city of Kolkata. A language that is considered not authentic, not from the linguistic sensuousness that reveals the world around us in signs and metaphors, but a language developed for a very specific or particular purpose: commerce.

My mother used to speak in pure Noakhailya language, the language of the people of Noakhali, full of wit, humour and subtle metaphor. This is my matribhasha, my mother tongue. While she used to express her love in Noakhailya language for her children she could articulate the words and sentences in such a way that I still claim with my Noakhailya chauvinism that none could express motherly affection except in sweet Noakhailya language. I grew up loving this beautiful language and soon noticed that every dialect has certain unique quality that is intricately connected with social formation, ecology, and history and above all cultural and knowledge practices. Knowing this fact did not hurt my Noakhailya pride; rather, over the years, the more I studied language the more I had to accept this truth with humility and profound interest to other dialects. Without being told by anthropologists or cultural historians, one can easily notice that language or speech acts are different by different communities as well as by status, class, and gender or by other determining factors. These facts are more or less known to social linguistics, however, the connection between language, ecology and knowledge practice is an area that has only recently come to attract attention.

I now work very closely on a day-to-day basis with farming communities engaged in biodiversity-based ecological agriculture. Bio-diverse agrarian practices are rich historical traditions of this deltaic country. The wealth, richness and global significance of such practices are only recently revealed because of advance in biological and molecular science. More these connections are studied and brought to the mainstream more they open up possibility of ensuring new advance in science and technology based on farmer-led research. Such research is able to ensure food sovereignty of Bangladesh, but perhaps also the other countries at the same time since creating bio-diverse ecological environment for the maximisation of the productivity potential of nature is not dependent on ‘gene’ but to the total environment where traits are expressed.

Bangladesh is rich in biodiversity and the potentiality of nature is simply phenomenal, if we learn how to unleash her power. However, that is not possible by industrial food production system, it implies we must move away from the environmentally-destructive chemicals including fertilisers, pesticides or biocides and it is criminal to waste our water resources in the aquifer polluting environment and health with arsenic contamination. This is what the present military-backed regime is doing, an insane path that sooner or later will permanently destroy our agriculture, while there are ample evidence that advance bio-diverse agrarian practices are possible to grow more food, fibre, medicines, fuel wood and construction materials. This will require that we ground our science and technology practice on the authentic foundation of a knowledge system developed within the ecological paradigm of Bengal, and not on industrial food production controlled by few trans-national corporations of the world.

Bangladesh is already bleeding because of the piracy of the rich biological resources and now the present ‘caretakers’ are rapidly engaged in destruction of the agrarian foundation by violently transforming rural areas into plundering grounds for seed companies, technology vendors and NGOs who are selling proprietary seeds and forcing farmers to accept those on (micro)-credit. With the support of the anti-people regime, not accountable to the people, they are powerfully manipulating the media claiming that commercial hybrid seeds are the solution of our food problem. These seeds need massive chemicals, pesticides and groundwater and totally destroying the existing seed system of the farmer upon which the agrarian production and economy has historically been dependent. The destruction the present policy of the ‘caretakers’ will eventually be a nightmare for Bangladesh, as well as for the ‘development partners’. These are issues that need to be addressed more in detail separately, but I raised the issue to highlight a point that we hardly can see: the connection between ecology, environment, culture and agrarian civilisation.

The dominance of the so called ‘promit’ Bangla also signifies erosion of our knowledge depositories that are embedded in our rural oral culture. What I would like to argue is that the idea of ‘language’ as a homogenous standard system that one learns from schools reading textbooks and the implicit notion of ‘education’ that implies unlearning the oral linguistic practices or local dialects is a dangerous notion indeed. The cultural and knowledge practices of a community who have been historically feeding us and maintaining ecology and environment for the future generations have done all their innovations, thinking and memorisation in a dialect that is specific and experiential. It is crucial that we turn our interest to this issue before it is too late.

When I need words to express or articulate agrarian practices or ecological or environmental terms, the literary Bangla is poor compared to the language that the farmers use. I wonder whether the dominance of the language of a particular class also creates conditions for environmental and ecological erosion. Local language and the knowledge practices of a community are crucial for survival. Once we realise the security and survival issues we could also understand why literary Bangla, or as it is called ‘promit” or standard Bangla, which grew within the commercial milieu of colonial Calcutta, is termed ‘commercial Bangla’ by agrarian communities I know very intimately. It is a form of cultural resistance against the processes of erosion and decay of knowledge practice embedded in oral communicative dynamics and stands in opposition to printing or standard texts.

To provide a simple glimpse of what we are talking about, we can simply take note of the various names of rice varieties used by farming communities; they surprise anyone because of linguistic innovation, taxonomic classification and metaphoric implication. Naming seed varieties is simply a phenomenal and brilliant act and scientifically could also be used as ecological descriptor in contrast to the breeders descriptors used by scientists trained in industrial food production. As a genuine student of the farmers the farming community awarded me with immense learning appropriate for agriculture, ecology and environment. Imagine, we had, as scientists claimed, nearly 15,000 varieties of rice.

However, some scientists argue that genetically speaking they are much less, since the same variety is named differently in different areas. It does not mean that such farmers’ lot, co-evolved with other species and varieties in farming practices are ‘same’. What these scientists are totally missing is the multiplicity in varietals or gene expression of a variety in a particular environment, ecology and farming practices – a knowledge that are extremely vital to develop agrarian planning, production, knowledge practices and culture. So the farmers’ name does not suggest so-called ‘pure line’ or pure variety – but knowledge of a variety that expresses differently in different environments.

This is the reason why ecological scientists in contrast to the industrial food producers and the trans-national corporations make scientific distinction between ‘breeders’ descriptor and ecological descriptor. The former is integral to industrial food production systems while ecological ‘descriptors’ are related to bio-diverse farming practices. These are names or categories used to capture the nuances of ecological, environmental and biological richness and wealth of our agriculture. The latter captures the ‘whole’ in unique environment while the former manipulates part – ‘genes’. The farmer’s movement that I am now involved with, known as Nayakrshi Andolon, cultivates nearly 2000 varieties of rice. Imagine, all these varieties has ‘name’ – all in Bangla, implying sharp or subtle nuances that could be used as ecological descriptor and key to the understanding of biodiversity-based ecological farming practices.

If language is part and parcel of diverse knowledge and cultural practices and product of social interactions where ‘commerce’ is only one of the socialising contexts or specific form of interaction – the overemphasis on the ‘standard Bangla’ or promit Bangla is to be seen as question related to class and power. Rightly, standard or promit bangla came into being as the product of colonialisation, capitalism and urbanisation that also produced a particular class and their literatures, imaginations, knowledge practices and class power. The historically specific form such interaction obtained is also directly linked with Gutenberg’s invention, i.e. printing technology. Communities imagining them as belonging to a ‘nation’ composed of ‘people’ or ‘population’ conceptualised in abstract, is very recent indeed. Nationalism or imagining ourselves belonging to an identity determined by language, homogenised culture or ‘nation’ directly contradicts the experiential perception of rural communities where people do not exist in abstract, not as number or population, but with specific names with parental link and places. Such imagining a population as ‘abstract’ nation is determined by the rise of the market and the printing technology.

If we understand differences as historically or contextually determined, we hardly need to argue. My argument here is not that whether we should not be imagining ‘nation’ and remain eternally bound to rural consciousness. My point is much more simpler: (a) from such historical understanding one cannot conclude imagining ourselves as ‘nation’ in any way proves a ‘progressive’ consciousness or in other words place-bound and experiential consciousness of farming communities are ‘backward; (b) that idea of language as a homogeneous phenomenon is problematical.

Having said this I do not conclude that ‘promit’ Bangla is something ‘bad’ that we should avoid, rather what we should do is activate a dynamic relation between the rich depository of knowledge in the our local dialects and weight of standardisation and homogenisation. Dr Shahidullah is the only person I know is determined to highlight the importance of local dialects. He was right, simply because he insisted that language is a living phenomenon and not a static affair. His dictionary on local language is a phenomenal step in exploring knowledge inscribed in local terms and notions. The critique of promit Bangla is not to argue that we should write and communicate only in local dialect. These are sterile logic and facile arguments. Language by nature belongs to our creative faculty and we must keep on exploring the language in many different ways since human communities are immensely creative.

My idea of matribhasha has nothing to do with the politics of identity. I am a nationalist only to the extent it contributes to the diversity of communities, nations, languages, cultures in order to constitute a global community. My interest in living local dialects is dictated by my interest in ecology, experiential knowledge and innovative knowledge practices that can invent, reproduce and maintain and thousands species and varieties in our ecosystems. I will not deny that I have some elements of chauvinism for such a rich bio-diverse agrarian culture and indeed I am proud of our farming communities since they are the one who understand from an immediate and experiential stance what does it mean by ‘matribhasha’.

14.2.08

The Millet

Sometimes words do not fit, but nevertheless are used to describe matters that need understanding. This leads to confusion for those using them, it is doubly annoying if we use them ourselves to describe ourselves.

Time and time again folks have argued about the use of alienating language and categorisation to mutilate the meaning and essence of this world. For example the meaning of the word 'moderate' in the context of government speaking about Muslims they would like to breed. This term is seperate from a more religious rendering of the levels of faith, which from low to high are Muslim, Mu'min and Muhsin. These levels (and others) are in our teachings and in our common sense. I pity the fool who brings up their child/institution/country according to the going politically expedient definition of moderacy from those who dont wish us the most blossoming of times.

And so onto 'the community', because that is why i'm writing this post. Its actually a millet. Historically the millet system was used for different communities to organise themselves during the Ottoman times. Maulana Husain Ahmad Madani wrote about the millet, distinguishing it from qaum (nation) in that it had a religious commonality running through it. Maulana Madani was one of those sages who we probably should have listened to before partition. Yahya Birt writes on him here.

I like it because i think it can help believers in the Occident to finetune their selfanalysis on their own terms. It originates from our own traditional ways of thinking about collective life. It is even mentioned in the quran, apparently 15 times. You can use it to describe a school of thought or a creed.

There is no unified muslim community here, think of Prophet Noah's Ark but with slightly different demographics. Theres a diversity in ancestral geography, kinship, religiosity, taste and class patterns that on one hand is amorphous, without structure, but looked at from a different perspective, is perfectly normal considering Our cosmopolitan history. Understanding this millet, this rapidly formed and immigrated millet, with simplifying policywonk doublespeak is not going to work or get the best out of it.

The Millet in the UK doesn't really know itself too well. University was a good, pretty ramdomised knowing point. Religious institutional life also, but that tends to be more of a localised thing. Allow the web. This getting to know itself will take a lot of time, but it is... as the dude said 'inevitable'.

Time and time again folks have argued about the use of alienating language and categorisation to mutilate the meaning and essence of this world. For example the meaning of the word 'moderate' in the context of government speaking about Muslims they would like to breed. This term is seperate from a more religious rendering of the levels of faith, which from low to high are Muslim, Mu'min and Muhsin. These levels (and others) are in our teachings and in our common sense. I pity the fool who brings up their child/institution/country according to the going politically expedient definition of moderacy from those who dont wish us the most blossoming of times.

And so onto 'the community', because that is why i'm writing this post. Its actually a millet. Historically the millet system was used for different communities to organise themselves during the Ottoman times. Maulana Husain Ahmad Madani wrote about the millet, distinguishing it from qaum (nation) in that it had a religious commonality running through it. Maulana Madani was one of those sages who we probably should have listened to before partition. Yahya Birt writes on him here.

I like it because i think it can help believers in the Occident to finetune their selfanalysis on their own terms. It originates from our own traditional ways of thinking about collective life. It is even mentioned in the quran, apparently 15 times. You can use it to describe a school of thought or a creed.

There is no unified muslim community here, think of Prophet Noah's Ark but with slightly different demographics. Theres a diversity in ancestral geography, kinship, religiosity, taste and class patterns that on one hand is amorphous, without structure, but looked at from a different perspective, is perfectly normal considering Our cosmopolitan history. Understanding this millet, this rapidly formed and immigrated millet, with simplifying policywonk doublespeak is not going to work or get the best out of it.

The Millet in the UK doesn't really know itself too well. University was a good, pretty ramdomised knowing point. Religious institutional life also, but that tends to be more of a localised thing. Allow the web. This getting to know itself will take a lot of time, but it is... as the dude said 'inevitable'.

12.2.08

The Taqwacores

So a white punk (Micheal Muhammad Knight) in the US becomes Muslim and for some reason goes to learn about Islam in an Islamabadi madrassa in Pakistan. He gets the chance, but for some reason doesn't go on a 'field trip' to Chechnya and returns home.

He writes the Taqwacores as what he thought would be his parting broadside to a religion he loved, but ends up sticking with it mA. The book centres on a houseload of punk muslims who apparently represent several trends present in Muslim life.

Only its all so bluddy extreme and decadent. Iranian guy with tatoos everywhere, evil woman cloaking her evil ways in a patched up niqab, indonesian chap called imam fasiq who sits on the roof smoking blunts reading the quran and a charismatic punk genius who gets killed in the most messed up finale that a Muslim mind could ever conjure up. Interestingly the narrative is presented from the point of view of the ubiquitous pakistani engineering student. This is probably his intended audience though nobody has ever intelligently interviewed the man. One character I really laughed at the patheticness of was the wannabe-bohemian Bangladeshi art student girl. Eurgh.

He is no Rushdie, he knows he's crossing Our unwritten redlines, but isn't being hateful. You can tell this by the scene when they all go chillout and pray in a mosque. In real life he has been used, seen through and publically discredited the naff 'Muslim Wakeup!' proregressive thing in the US. He has even had some legal problems with the hoity toity 'Muslims for Bush' girl. One of my elder bhaiya's told me once that 'Fugstar, you need to know that they (the taqwacore lot) are completely nuts', but I still hold a candle for his kind because they produce stuff that seems to have some meaning to it. Some of the scars they bear I guess I share.

There are a lot of lessons in the spaces he has moved through and the things that he writes about (the complementary flavours of islamic identity, practice, real Muslim life, Ummah, innovation and cultural schitzophrenia/synthesis). But reading his stuff is pretty painful, even if you aren't Muslim. Part of me wants everyone to have read it so I can ask them who's fault Jehengirs death was... but the other part of me wants to cringe and whince at the prospect of putting someone dear to me through the traumatic experience of reading it.

It has been said that many have misunderstood the book, especially the bunch of yaars who used it as a motivation to setup a band called 'The Kominas'. But others have come up with something half decent and there should be no mistake in identifying Sean Muttaqi as the firestarter of all of this. One cute sidenote is how the british version was a little censored because it was brought here after the cartoon mayhem. It is still very sick and needlessly crass though, it's hard to imagine what critera they used to remove certain passages, but the fact they bothered deserves some kudos.

In an age where innocent civilians are stumbling upon 'Ed's' pile of bum and drawing conclusions about The Millet, I reckon 'The Taqwacores' is good for a laugh, if not just to be put back in touch with one's more Victorian values. Other books for interesting adventures around the Ummah are Ziauddin Sardar's 'Desperately Seeking Paradise' and Akbar S Ahmed's 'Journey Into Islam'. Ahmed's one oozes finesse and a real love and regard for Islamic historical trends, Muslim people and the journeys they take, while Sardar's is a little more erm ... 'self centric' (its semi autobiographical after all), playful and fiesty. Both are written by people, from my point of view, of far greater oversight, substance and knowledge.

9.2.08

Archbishop, Shariah and Loya Jirga

There has been a big symbolic kerfuffle concerning the Archbishop of Canterbury's speech on "Civil and Religious Law in Britain - A Religious Perspective". He is quite the Professor Dumbledore, only the british arent too quick to recognise this fact.

Yahya Birt has written on the matter here . If you'd like to learn some more about Shariah, Bite Size Islam is doing a good service. He starts with the objectives of the sharia, which is as good a place as any to start from and builds from there.

Its quite saddening to see a motley crew of opportunists and stupid people jumping into a field they are ignorant about to stab Islamic Legal Culture as the barbarianism at the gates. It is also quite revealing to see how crass 'femenism' seems in the lips of neocons and erm.. 'cultural muslims'. I guess it appeals to the media confusion machine because it links to so many of their other creations over the years.

Im not a lawyer, so when i think of better dispute resolution and mediation in families and communities i think of wise counsel, based on principles, stocked with experience and spirit. Just like there is a philosophy and meaning to the act of making a can of coke, so there is to solving any human problem.

At present, the Millet of Britain doesn't not know itelf and is not mature enough to selfconfidently pull of a loya jirga (to use someone else's term) type space of its own. In this space festering divisions could be fixed creatively, eid on one day would be sorted and the great questions of our time addressed with the seriousness and devotion they require, rather than with soundbites and white lies. The demands of such a space are higher than the Millet can acheive at present.

Yahya Birt has written on the matter here . If you'd like to learn some more about Shariah, Bite Size Islam is doing a good service. He starts with the objectives of the sharia, which is as good a place as any to start from and builds from there.

Its quite saddening to see a motley crew of opportunists and stupid people jumping into a field they are ignorant about to stab Islamic Legal Culture as the barbarianism at the gates. It is also quite revealing to see how crass 'femenism' seems in the lips of neocons and erm.. 'cultural muslims'. I guess it appeals to the media confusion machine because it links to so many of their other creations over the years.

Im not a lawyer, so when i think of better dispute resolution and mediation in families and communities i think of wise counsel, based on principles, stocked with experience and spirit. Just like there is a philosophy and meaning to the act of making a can of coke, so there is to solving any human problem.

At present, the Millet of Britain doesn't not know itelf and is not mature enough to selfconfidently pull of a loya jirga (to use someone else's term) type space of its own. In this space festering divisions could be fixed creatively, eid on one day would be sorted and the great questions of our time addressed with the seriousness and devotion they require, rather than with soundbites and white lies. The demands of such a space are higher than the Millet can acheive at present.

5.2.08

Large Amounts dont grow on trees...

But sometimes they fall from them...

Some beautiful soul has purified his wealth and made a difference to the lives of the cyclone affected deshis by donating $130 million through the Islamic Development Bank. $110 million for rebuilding schools and shelters and $20 million for livelihood support.

In true class they have remained anonymous. Allah reward them for it and see to it that the contribution is best used.

There was an article written about desh recently, it made me quite angry as it was linking 'rising islamic radicalism' and 'climate change' to the survival of the country. Maybe the chap had a point but it was the cheap policy wonk points scoring nature of it that pissed me off most. Congratulations secularist lobby for playing up deshi fundoness.

Theres a part in the article where he figures that Bangladeshis are nearly always pro american, except for on the climate change issue. I guess this is because he's trying to play on his countrymen's heart strings. On the other hand so many Deshis in the states swallow the american dream thing hook line and sinker. They swallow it and try to spread it even when they are not in america. But my favourite snippet is his take on Islam in desh, 'just one element of Bangladesh's rich, heavily Hindu-ized cultural stew'. I guess its easy to see the kind of people he has been speaking with and the values they hold. This clique, which reproduces itself with aid money has to spin around observers to ensure its survival.

And thats the crux of the matter. No country ever rose on the back of anyone elses charity.

Oh, and i'm getting the feeling that Asma Jahangir of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan is a bit of an annoying yaar type. She featured embarrasingly appalingly on BBC Radio 4's start the week programme with Andrew Marr last week.

Some beautiful soul has purified his wealth and made a difference to the lives of the cyclone affected deshis by donating $130 million through the Islamic Development Bank. $110 million for rebuilding schools and shelters and $20 million for livelihood support.

In true class they have remained anonymous. Allah reward them for it and see to it that the contribution is best used.

There was an article written about desh recently, it made me quite angry as it was linking 'rising islamic radicalism' and 'climate change' to the survival of the country. Maybe the chap had a point but it was the cheap policy wonk points scoring nature of it that pissed me off most. Congratulations secularist lobby for playing up deshi fundoness.

Theres a part in the article where he figures that Bangladeshis are nearly always pro american, except for on the climate change issue. I guess this is because he's trying to play on his countrymen's heart strings. On the other hand so many Deshis in the states swallow the american dream thing hook line and sinker. They swallow it and try to spread it even when they are not in america. But my favourite snippet is his take on Islam in desh, 'just one element of Bangladesh's rich, heavily Hindu-ized cultural stew'. I guess its easy to see the kind of people he has been speaking with and the values they hold. This clique, which reproduces itself with aid money has to spin around observers to ensure its survival.

And thats the crux of the matter. No country ever rose on the back of anyone elses charity.

Oh, and i'm getting the feeling that Asma Jahangir of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan is a bit of an annoying yaar type. She featured embarrasingly appalingly on BBC Radio 4's start the week programme with Andrew Marr last week.

1.2.08

Writing While Underage (WWU)

I came across the concept today for the first time, that writing with 'false' authority when you are young, learning and probably stupid is normally regretted in later life. There's also a parallel with entrepreneurs who fail with your money, though people remember losing money more that folks chatting ring i suppose.

This is due to all the misleading done in the process and the damage done by quarterbakedness. In these days of hurried, amplified verbal noise and the proliferation of chaff (not least my own) it is hard to consider WWU an actual impediment to understanding and development. But i guess it is amongst others.

Looking at scholars who i love, theres something about their steadfastness and patience in the face of entropy that thrills me. Whilst politicians, colomnists, journalists and silly bluggers change their minds and whispers to suit various contingencies, scholars have a constancy and the best have a self accounting. This is something which comes with rooting i think, its not a stubborn feature... its just quality.

This is due to all the misleading done in the process and the damage done by quarterbakedness. In these days of hurried, amplified verbal noise and the proliferation of chaff (not least my own) it is hard to consider WWU an actual impediment to understanding and development. But i guess it is amongst others.

Looking at scholars who i love, theres something about their steadfastness and patience in the face of entropy that thrills me. Whilst politicians, colomnists, journalists and silly bluggers change their minds and whispers to suit various contingencies, scholars have a constancy and the best have a self accounting. This is something which comes with rooting i think, its not a stubborn feature... its just quality.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)